Facilitating Community Acceptance of Urban Air Mobility

11.15.2021 | HMMH |The first two decades of the twenty-first century have seen an increasing rate of urbanization. According to the United Nations, in 2016, an estimated 54.5 percent of the world’s population lived in urban settlements; by 2030, that number is expected to increase to 60 percent, and one in every three people will live in cities with at least half a million inhabitants. As a result, the need for safe, efficient, and affordable travel has pushed transportation planners to look above the surface of cities to the air. Urban Air Mobility (UAM) has emerged as one way for cities to enhance mobility to, from, and within city centers. UAM includes the enhanced use of existing helicopters, as well as their eventual replacement with electric vertical take-off and landing (e-VTOL) aircraft. The vision for UAM is that these e-VTOL aircraft will be flown by human pilots, as well as autonomously. UAM falls under the umbrella of Advanced Air Mobility (AAM).

This white paper presents preliminary thoughts, insights, and strategies to facilitate community acceptance of UAM operations, and identifies issues of concern for various stakeholders invested in its growth. These stakeholders include aircraft operators and airports; the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) as steward of the National Airspace System (NAS); and the cities and communities where UAM will operate. UAM will require new infrastructure within and around cities to accommodate these new aircraft. Operational models considered by UAM operators include functions like those of an airport sponsor, including provision of a takeoff/landing area for aircraft (vertiports); facilitation of mode changes from aerial to surface-based transportation; and provision of terminal facilities for passengers.

Because UAM will be operating in new areas, community engagement must go above and beyond the legacy aviation industry’s current best practices. We believe that achieving successful integration of UAM into the NAS involves the consideration of different tailored messaging. These strategies may differ in content, form, detail, and objectives based on the role each specific audience plays, while still reinforcing broader and consistent themes. Such varied potential audiences include UAM Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs, such as Joby, Jaunt, Bell, etc.), UAM operators (Blade, Uber, etc.); airport sponsors; FAA officials; elected and appointed officials; and members of the general public, including potential UAM customers and those residing within the line of sight of UAM operations.

Cities and local governments will play a major role in obtaining public acceptance that goes beyond. Cities and elected officials will need to work with their constituents and the UAM industry to promote a close working relationship to avoid the types of issues that arose from the FAA’s implementation of NextGen aircraft procedures. Operators and manufacturers of UAM may wish to engage the FAA on the development of a process like for developing noise-compatible land-use guidelines for vertiports. Physical and operational differences between UAM vehicles and legacy aircraft may argue for a metric other than the A-weighted DNL currently in place. Proponents of UAM integration into the NAS have an opportunity to shape these guidelines in a manner that reflects and respects these differing characteristics. This would provide validation to local land-use regulatory authorities that local planning and zoning restrictions based on these guidelines would be grounded in traditional concepts of protecting public safety, health, and welfare; prevention of nuisances; and facilitating orderly and efficient development in a manner that conserves scarce public resources.

Legacy Airport Engagement

The goal of legacy airport engagement is to educate and collaborate with existing airport industry stakeholders on potential noise and annoyance issues related to UAM, to assist these stakeholders in planning for the integration of UAM into the aviation system, and to engage stakeholders as advocates for UAM. Engagement with airport sponsors and their staffs, and whose missions are advocacy and research programs supporting airport operations offers opportunities to leverage lessons learned from legacy advocacy and engagement activities. These organizations include the following:

- Airports Council International – North America / American Association of Airport Executives (ACI-NA/AAAE): UAM operators and manufacturers should attend and speak at airport industry conferences to provide updates on technology, anticipated community issues, etc. HMMH is well-equipped to provide airport industry contacts, identify the best venues for accomplishing integration and acceptance goals, and support their interactions with local airports.

- Transportation Research Board (TRB): The TRB has several technical committees that are good venues for additional communication and networking. HMMH can TRB contacts and identify the best workshops and seminars.

- Aviation Week: Providing support to the industry, publications such as Aviation Week are critical to maintain on-brand messaging for UAM, and the infrastructure that will support its proliferation.

- NASA UAM Noise Working Groups: OEMs should continue their participation with NASA because much of the theoretical and applied scientific basis that ultimately will inform federal policy on preventing, mitigating, and remedying annoyance from aircraft operations will likely originate from this group’s efforts. HMMH is already engaged in this working group, most notably by contributing to a future NASA Technical Paper, “Urban Air Mobility Noise: Current Practice, Gaps, and Recommendations”.

Community Engagement

Community acceptance strategies must focus on educating community leaders, policy influencers, and members of the public about noise issues related to UAM with transparency and presenting information in simple, understandable language.

Research shows that only about 30% of individual annoyance with aircraft noise can be correlated with acoustic properties of aircraft; the rest can most likely be attributed to non-acoustic factors, such as attitude toward the noise source. Thus, UAM operators must establish relationships in the communities in which they intend to operate so that stakeholders perceive UAM operations favorably. HMMH has a long and successful history of working with communities and aviation stakeholders to present and explain changes and impacts to flight paths, noise contours, and other issues associated with community acceptance.

Proponents of UAM integration should first leverage existing regulatory and policy frameworks to inform engagement strategies, drawing upon existing organizational relationships. One approach is to work with community representatives in proposed UAM markets to understand the “hot button” issues in those communities and to identify sub-communities that tend to react most negatively to noise issues. Once communities have been identified, we would suggest that this effort be expanded to a retail level by reaching out even further into neighborhoods, homeowners associations, and other community groups. It would also be worthwhile to attend community events (e.g., farmers markets, sporting events, and other venues that attract members of the general public) to socialize the operators’ presence in the community and to disseminate information to the community. This effort would be supported by the communications strategy and collateral described in the sections below.

Develop Tailored Communications Strategies & Materials

UAM proponents should develop tailored communications strategies for elected officials and communities that recognize the different roles, responsibilities, and interests of each group. These strategies should encompass the immediate neighborhood where operations will occur and the wider community. For example, strategies in a neighborhood where a vertiport will be built will be different than those required for a neighborhood with an existing airport.

Outreach methods include press releases and interviews with the media, establishing social media channels, outreach to schools, establishing a citizen science project(s), websites, noise auralization and visualization, videos, brochures, etc. All materials should use plain language and effective graphics to clearly and briefly communicate desired messages. These should be deployed through the various communications channels established in the communications strategy according to an intentional plan. Such collateral should also be tailored according to the needs and culture of each community.

These strategies should include community forums where elected officials, community members, and other community stakeholders can engage with operators, OEMs, and other UAM proponents, in significant, meaningful community dialogue. We have participated in community roundtables across the country as facilitators and technical experts and recognize that each community and its sub-communities have different concerns. Engaging communities at the micro and macro levels allows for all concerns to be heard at an adequate level of detail, rather than attempting to address all concerns at broad meetings. Acceptance of decisions and outcomes increases when the affected community feels that their concerns have been heard and understood by decision-makers, even if the concerns have not been fully addressed.

Finally, these strategies must be ongoing and evolving, and stakeholders should be forward-thinking to address future concerns. Communications channels need to remain open throughout UAM presence in a community to ensure that concerns and issues are addressed over an operator’s entire tenure and not just at the onset.

FAA Engagement

The FAA has primary authority over the certification of UAM vehicles, integration and/or separation of UAM operations with the NAS, and evaluation of the operational and environmental effects of UAM operations at airports and other facilities. The goal of FAA engagement is to ensure the certification and implementation of UAM is as smooth and comprehensive as possible. We suggest proactive and immediate engagement with the FAA to move policy toward acceptance and integration. UAM proponents should provide data and research the FAA needs to help move policy from concept to reality. This research falls into three key areas: metrics and annoyance research to address community acceptance issues, UAM vehicle certification, and modeling to meet regulatory requirements.

Responding to Communities

HMMH believes extensive engagement, communication, and training for the FAA’s Noise Ombudsmen and Office of Environment and Energy (AEE) staff will be required to assist the FAA in responding to concerns raised by airports, communities, and other stakeholders. Our experience with the FAA’s implementation of Performance Based Navigation (PBN) and associated air traffic procedure and flight path changes indicates that early, proactive engagement is critical. Based on our experience with PBN implementation and stakeholder and community engagement on other programs, we can suggest strategies, materials, and discussion topics that can facilitate and expedite this engagement process. An important lesson learned from our work on the implementation of NextGen procedures is that community engagement should not be avoided until communities react, but rather should be proactive in informing communities before implementation. This process is much more likely to result in community “buy-in” for UAM operations. The importance of engaging elected officials and cities involved in this process will lead to community acceptance and understanding of the importance of UAM operations for themselves, and for their neighbors.

Metrics/Annoyance Research

Noise and annoyance metrics measure and quantify noise effects on the operational community and environment. Current noise and annoyance metrics may not fully capture the concerns and issues arising from UAM operations. This requires investigation into new or additional metrics that encompass the full spectrum of UAM concerns.

Evaluation of Non-Conventional Metrics for Annoyance

The FAA uses A-weighted metrics to evaluate community noise and annoyance issues, due to its strong correlation with human hearing. A common A-weighted metric is the Day-Night Average Sound Level (DNL), which averages noise that occurs over 24 hours, adding a 10-dB weighting to noise events occurring during the night and early morning hours. Other common A-weighted metrics include Time Above (TA), referring to the time that noise levels exceed a specified sound threshold; and Number Above (NA), referring to the number of noise events exceeding a specified (single-event) threshold level. The FAA relies on Effective Perceived Noise Level (EPNL) for certification of aircraft.

FAA requires the use of DNL for aviation noise exposure studies conducted for airports, and for land use compatibility planning around airports. FAA guidance states that all land uses are compatible where aircraft DNL is less than 65 dB. Recent research suggests that other metrics may better suit unusual noise conditions such as those presented by UAM. One such area of study addresses the effects of low-frequency noise on annoyance and the challenge in finding appropriate metrics to account for this.

A significant challenge for UAM acceptance will be to first identify and demonstrate the need, relevance, and accuracy of alternate noise metrics and to then work with the FAA to accept that these alternate metrics better correlate with noise and annoyance in the evaluation of UAM implementation.

Evaluate Potential Need for Additional Annoyance Research

HMMH conducted a pilot study of helicopter noise annoyance for the FAA in 2016, and FAA plans eventually to conduct a full research program on helicopter noise. Rotary-wing aircraft have significantly different acoustical signatures and operational characteristics as compared with fixed wing aircraft; since UAM vehicles, particularly in early phases of adoption, will likely resemble rotary-wing aircraft, the dose-response relationships used for fixed-wing aircraft may not yield the same predictive powers for vehicles used in UAM. Conducting and funding equivalent research for UAM is imperative. For a “new entrant” such as an e-VTOL, HMMH can anticipate research needs, similar to NASA’s proposed community response testing for its X-59 quiet supersonic demonstration, to apply to a prototype UAM vehicle or current UAM-style operations with helicopters.

Current research addresses annoyance following the concept of operations for traditional aircraft, which uses largely defined flight paths and defined schedules. The UAM concept aligns more closely with general aviation operations; however, given the stated intents of UAM, its concept of operations will result in more intimate involvement with surrounding communities. Its operational concept may also differ from what the general population has come to expect from air travel, since the on-demand and last-mile nature of UAM may result in flights at inconsistent hours, altitudes, and flight paths. HMMH recognizes that these differences will likely change the community’s threshold for annoyance and recommends that academic institutions, OEMs, operators, and other UAM stakeholders identify and conduct research programs addressing the effects of potential UAM concepts of operation, specifically on annoyance and the associated dose-response curve. Our studies on helicopter noise and community annoyance, among other work, positions us to assist with and provide advisory services, development, and execution for similar research programs.

UAM acceptance involves visual, privacy, noise and concerns associated with UAM-adjacent services such as increased foot and vehicle traffic to and from vertiports. Operators of vertiports will need to build access points; customers will need to reach these access points via public transit, private vehicles, rideshare, and other means. Operators should be cognizant of this secondary annoyance factor when developing and sharing plans with communities and other stakeholders. With our experience in noise and environmental analyses for comprehensive programs, HMMH is well-equipped to support and provide expert advisory services regarding such multi-modal considerations.

Standards and Certification

Operators and OEMs should continue to engage the FAA to establish a regulatory framework similar to the existing sub-parts of Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations Part 36 (14 CFR Part 36), which defines noise standards by aircraft type for aircraft certification. Once a uniform framework for a noise certification process tailored to UAM operations is in place, a process for certification of specific aircraft designs and individual aircraft would follow. Such a process will likely include the use of noise metrics and processes that differ from those used for legacy aircraft.

UAM vehicles will differ in noise signature due to variations in airframes, propulsion methods, hardware, and other characteristics. Accurate noise modeling relies on the availability of adequate acoustical source data, which will need to be made available by the OEMs. HMMH understands that OEMs may want to maintain proprietary control over their acoustic source data prior to, and perhaps even following, certification and operation to maintain a competitive edge. This will require the FAA, OEMs, and operators to balance the proprietary nature of this data with the need to accurately characterize the noise associated with UAM fleets and operations. HMMH recommends that a noise certification standard for UAM account for the fact that colloquially in communities, if it is loud enough to be audible, it is loud enough to potentially annoy and inhibit community acceptance.

Certification, regulations, and requirements for UAM aircraft and their integration into the NAS need to have defined, established noise standards, similar to that of 14 CFR Part 36 noise standards, incorporated by reference in 14 CFR Part 23 airworthiness standards. HMMH believes that stakeholders would benefit by proactive involvement with standards committees and other policymakers to influence and advance the direction and content of these regulations.

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Noise Modeling to Meet FAA Requirements

When planning new infrastructure such as vertiports, or adding UAM operational capacity at airports, it is foreseeable that UAM operators and local jurisdictions (as a petitioner) will have to prepare an environmental study that facilitates compliance by a federal agency with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). If so, there are several noise issues to consider:

FAA Order 1050.1F Requirements

FAA Order 1050.1F, Environmental Impacts: Policies and Procedures, requires the use of the FAA’s Aviation Environmental Design Tool (AEDT) to prepare noise analyses under NEPA, and sets thresholds of environmental significance at a 1.5 dB increase in noise-sensitive areas that would be exposed to DNL 65 dB or greater. This is outside the issue of determining the best dose-response metric; this is a federal requirement that is unlikely to change in the near term. Operators and stakeholders need to be aware of these requirements when considering widespread operation within a geographical area.

Advanced Acoustics Model (AAM) v. Aviation Environmental Design Tool (AEDT)

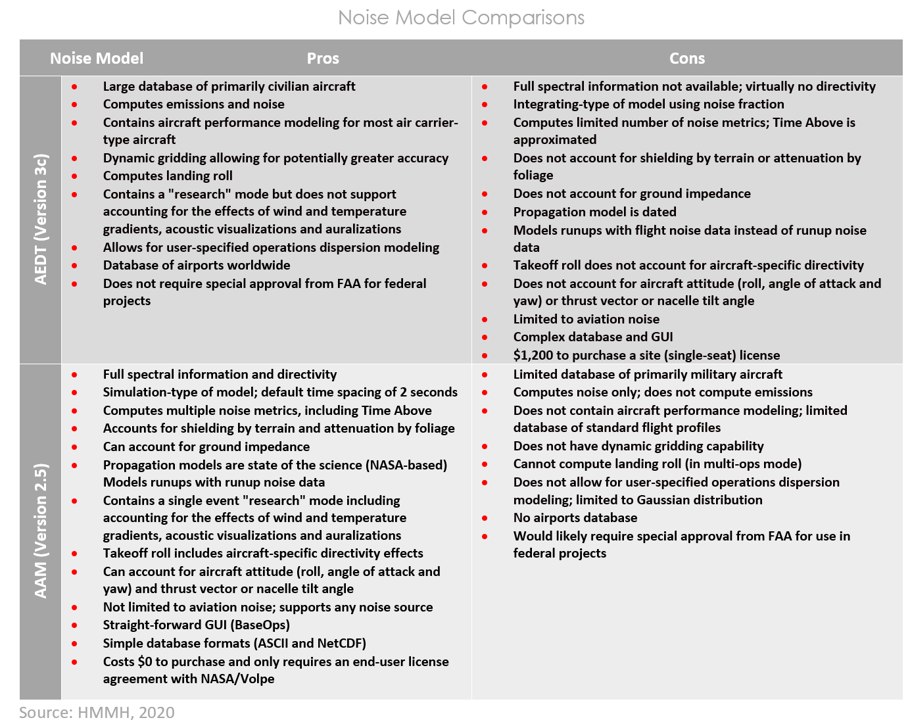

Currently, AEDT does not compute non-standard metrics. In addition to AEDT, UAM operators and OEMs have worked with NASA and Volpe to modify the Advanced Acoustics Model (AAM) to compute experimental non-standard metrics. If a non-standard metric is chosen for UAM vehicles, the FAA would need to confirm AAM as an acceptable modeling method for UAM vehicles.

Conclusion

UAM offers one solution to the problem of maintaining and improving effective movement within growing urban centers. However, to fully leverage UAM as part of this solution, significant regulatory and acceptance hurdles must be addressed. Community acceptance of UAMs will be critical to their success, and HMMH recommends that OEMs, operators, and other UAM stakeholders adopt a comprehensive, positive, and interactive community engagement strategy to foster this acceptance. HMMH also recommends that the strategy be tailored to address needs and concerns that are specific to each community and that the strategies continue and evolve to address changing concerns.

Standards development, certification, and integration with existing infrastructure are required to achieve UAM acceptance. Additional metrics may be needed to adequately describe the unique noise, annoyance, and community concerns related to UAM. We recommend the extension of existing metrics and new research in these areas. Since these operational concepts differ from current aviation operations, unique solutions will have to be developed through partnerships with local communities, including elected officials and community groups, and land use agencies.

UAM provides a promising alternative to traditional mobility but presents several challenges relating to integration into the NAS and to community acceptance. A significant amount of research and work is required to allow UAM to smoothly integrate into the NAS. With an industry roadmap of key areas of focus to drive research, standards development, and other work in these areas forward, this integration and socialization can move forward effectively.

Note: Footnotes are available in the downloadable PDF at right.